1. U.S. Wheat Grades

Tab. 15 summarizes the grade requirements for wheat.

There are 5 wheat grades for good quality wheat. All other wheat, i.e.

wheat that

– does not meet the requirements for grades U.S. Numbers 1, 2, 3, 4 or

5; or

– has a musty, sour, or commercially objectionable foreign odour

(except smut or garlic odour); or

– is heating or otherwise of distinctly low quality, is classified

U.S. sample grade.

|

Tab. 15: Grades and grade requirements for wheat

|

2. Milling Industry Overview

The U.S. Milling Industry has undergone dramatic change from any

perspective, both from a historical and a current business view. North American

milling is without question a competition- based market. It has been shaped and

moulded by the economic forces created by the combined decisions of the

consumers and producers of flour. In order to put these changes into a context

to which we can all relate, a set of terms common to the U.S. market will be

used to bring some clarity to this subject matter.

• Annual Wheat Flour

Production:

Total flour produced by all U.S. milling companies combined in one

calendar year. Expressed in Cwt 8.

• Daily Capacity:

The amount of flour capable of being produced by all U.S. mills in one

24-hour period. Expressed in Cwt (shown here in metric tonnes).

• Operating Rate:

A percentage calculated by dividing the "Annual Wheat Flour

Production" by the theoretical "Annual" 6-day capacity of the industry.

Expressed as a percentage

• Per Capita Consumption:

The amount in pounds of wheat flour consumed per person in the U.S.

This includes all forms of wheat-based food products and is calculated on a

disappearance basis. Expressed in lb per year.

Note :

8 1. A unit of

weight in the U.S. Customary System equal to 100 pounds (45.36 kg). Also called

cental, or short hundertweight.

2. A unit of weight in the

British Imperial System equal to 112 pounds (50.80 kg). Also called quintal.

Flour milling is clearly one of the world's oldest industries, for the

extraction of endosperm from wheat as a source of food was one of mankind's

first halting steps towards civilization. In America flour milling is among the

oldest industries; in fact the first flour mill was established in Virginia in

1621, or just 14 years after the settlement of Jamestown. In the 18th and 19th

centuries, as the U.S. grew and moved west, new flour mills were built as

virgin lands were cultivated and began producing large crops of wheat. As the

people moved west, so did the production of wheat and the milling of flour.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, as wheat growing became established

in the Great Plains, the mills in that area tended to become larger, and those

plants remained in operation well after the westward migration of people

spilled over the Rocky Mountains onto the West Coast. Even as the westward

migration to California, Oregon and Washington of the nineteenth century turned

into the flood of the twentieth, two of the three largest wheat flour milling states

were in the heart of the traditional wheat growing region – Kansas, which ranks

number one and Minnesota, which is number three (California has recently

replaced New York as number two; Anon., 1998).

Not only is flour milling one of the oldest industries in the United

States; it has also been one of the largest industries. In fact in 1900 flour

milling was the largest industrial classification in the United States, with

some thousands of small, mostly privately owned mills. This is no longer the

case. Today the number of mills has dropped to less than 200, most of these being

large mills. The number of companies owning mills has compressed even more

dramatically. If we look at the current status of the U.S. milling industry we

see there are at least four trends of some significance. The first trend is the

reduction of companies currently milling wheat into flour in the U.S. (Tab.

16).

|

Tab. 15: Grades and grade requirements for wheat

|

One of the clear effects of competition-based change is that there are

winners and losers. In U.S. milling, maybe "winner" doesn't describe the

existing milling companies as well as the term "survivor". As is true

in all business, we must look at a longer view to understand if a current

"survivor" is a true winner or simply the next market-place victim.

History is shouting that the number of milling companies in the United States is

in decline. Current economics seem to support a continuation of that decline. As

of this writing there are approximately 194 wheat flourmills operated by about

85 milling companies (Anon., 2000).

The second trend, which is tied to the first, is the reduction in the

number of operating mills in the United States (Tab. 16).

The message of Tab. 16 is that the U.S. demand for flour compared to

the available supply is limiting the financial return for milling companies. This

earnings pressure is causing milling companies interested in remaining in the

business to look for growth through acquisition. The goal of the acquisition is

to increase sales volume without increasing the corporate infrastructure

required to operate the company, thus allowing the remaining company to take

advantage of the increased scale through increased earnings. Tab. 16 also shows

the long-term change in the number of mills and in the average size of the

remaining mills since 1974. It is interesting to note that average mill size

has more than doubled while the number of milling locations has dropped to

slightly more than half. Again, it appears that in order to produce an

acceptable return for the company owners, a mill has had to increase the output

of a location in a greater proportion to its fixed cost structure. Much like a company has had to

add locations to increase its output in relation to its overall corporate size,

the individual mill has had to increase its output in relation to the fixed operating

costs of an individual location.

|

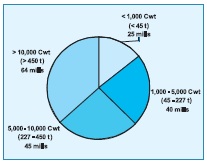

Fig. 18: U.S. Mills by daily flour capacity and market share (Anon.,

2005)

|

|

Fig. 19: Number of mills by daily flour capacity (Anon., 2005)

|

This third trend of increased mill size is understood better by

comparing Fig. 18 and Fig. 19. These charts further break down the number of

mills in operation and group them by overall size. While the average U.S. mill produces

just over 380 t of flour per day, the reality is that the largest number of

mills in the U.S. produces more than 450 t of flour per day. This further

highlights the fact that mills have had to get bigger to maintain or improve

their financial position. Finally, if we look at the amount of wheat ground by

all mills within a size distribution we can see that as expected the

largest mills also dominate the overall capacity of the country. In fact two thirds

of all wheat is ground by one third of the mills.

Mills and milling companies positioned well geographically and

strategically have survived to acquire those that have good geography but a

poor strategy. Those with neither good geography nor good strategies are

typically the mills abandoned.

The final trend is somewhat surprising. The U.S. industry has

continued to grow in overall daily capacity. While consolidation has taken out

numerous mills and milling companies, the opposite has happened with respect to

the ability of the industry to produce flour (Fig. 20). This chart shows that

there has been an upward trend in the capacity to produce flour in the U.S. for

the last 6 years of the last decade. While this has been an exciting time of

resurgence for the industry, the current condition is not one of widespread

optimism. Part of the issue has to do with the amount of capacity added in the

late 1990s. As many have said, the Western U.S. needed one new flour mill in 1999,

but 4 milling companies built it.

Some focus should be given to the U.S. wheat flour demand. Several

factors go together to create the overall demand for wheat flour in the United

States.

• Population

• Per Capita Consumption

• Dietary Perceptions

• Flour Use

|

Fig. 20: U.S. milling output versus U.S. milling capacity 3

|

The demand for flour in the U.S comes from two major factors. The

first is the U.S. population and the second is per capita consumption of wheat

flour based products. Flour and wheat based imports, while important, have been

largely flat over time and have been ignored in this analysis. Exports of U.S.

flour have played an important role in the strength of the U.S.

generally overshadowed by governmental policies and therefore are not

a good indication of the U.S milling industry's world competitiveness. Exports,

too, have been ignored as a part of the demand for U.S. flour and flour based

products.

|

Fig. 21: Change in population for U.S. states 1990 to 1999 (source:

U.S. Census Bureau)

|

The shift of population centres from North to South and East to West

has had the impact of shifting flour demand away from some of the North Eastern

and Midwestern mills towards mills able to send flour to the growing Western markets.

|

Fig. 22: U.S. flour consumption per capita by year 3

|

Per capita consumption is equally critical to a growing U.S. industry.

Remember, in the U.S. we measure the amount of flour consumed in one year, not

the wheat. In so doing we exclude the amount of wheat eaten by animals. The growth

in per capita consumption of flour has been one of the real success stories in

the U.S. food industry. U.S. flour consumption has grown by nearly 25% since

1964, and has fuelled the need for much of the milling capacity expansion. This

growth in demand has come about due to a couple of factors. The primary reasons

were that a favourable perception that "grain is healthy" was

combined with an American population that began to eat on the go. Meaning that

the meal is consumed away from home, often in an automobile, making time and convenience

extremely important. This has dramatically increased the use of wheat flour products

used as "meal carriers". Buns for hamburgers and hot dogs; tortilla wraps

for hand-held meals and sheeted bread products like pizza dominated the

consumption growth of the last three decades. The "grain is healthy"

viewpoint was further enhanced by the government's adoption of the food guide pyramid

(page 28) that describes a healthy diet as being based upon foods made from

grain.

One area of concern is the apparent levelling of this growth trend

that appears to have taken place over the last couple of years (Fig. 22). Much

of the concern lies in the unknown. No one is sure, but the speculation is that

we may have reached a plateau of consumption in the U.S. Others more optimistic

see this not as a plateau but as a slowing of the growth rate. In either case,

the growth rate of domestic flour demand has slowed to near stagnation, equal

to just that growth that has come from the increased population and government

aid donations. This will continue to challenge the U.S. milling industry to

make many tough decisions about capacity. The likely scenario is one of

continued consolidation in the number of companies, and the abandonment of

misplaced less strategic capacity. The U.S. milling industry is believed to be

healthy economically when the industry operating rate exceeds 90%. Any

reduction in demand or increase in supply in the near term could push the industry

into another round of consolidation.

However, an end to the consolidation will come. Over time the remaining

milling companies and mills will be less likely to overbuild capacity and repeat

the cycle of oversupply and consolidation. This belief is based upon the

assumption that with fewer companies making "capacitybalancing decisions",

better decisions will result. These surviving companies, hurt economically in this

recent period of capacity expansion, will be less likely to trigger another

state of over capacity.

Post a Comment