By : The Future of Flour

A. Pasta and Noodles in North America

By : J.A. Gwirtz, M.R. Willyard and K.L. McFall

In America, noodles – with only a few exceptions – fall into the category of pasta. Pasta includes products such as spaghetti, macaroni, lasagne noodles, shells, fettuccine etc.

These products vary greatly in shape and extrusion technology to create a desired shape. Most noodles are just variations in the shape of pasta.

One exception is homemade-style egg noodles, which are produced in a non-dried and frozen form, but are a very small part of the pasta market in the U.S. In North America pasta is mainly produced from durum wheat, most of which is grown in Canada and the northern United States.

However, frozen non-dried egg noodles that are produced to imitate homemade noodles can be made from soft or hard wheat flours. Durum is a vitreous kernel, amber in colour, that produces coarse semolina with properties that yield quality pasta products.

Generally speaking, high-protein durum wheat is desirable because vitreousness results in a greater yield of high-quality semolina for pasta production. Quality pasta is generally produced from 100% durum flour and water as the primary ingredients.

However, for various reasons non-durum flours may be added to replace part, usually a small part, of the durum flour. Other ingredients, such as eggs for egg noodles, are used to produce a variety of flavours and colours.

The process starts with the automatic press, which combines the mixing of flour, water and any other ingredients required for the specific product with kneading and extrusion of the dough.

This is a continuous process followed by a shaping mechanism to determine the shape of the extruded product.

After extrusion and shaping the pasta is conveyed to a drier for final moisture reduction to preserve the product and achieve stability during distribution.

Drying conditions (heat and humidity) must be carefully controlled in order to dry the pasta without altering the quality of the final product.

After drying, the pasta is cooled at carefully controlled humidity to protect its quality. Pasta quality is determined by flour quality and process control.

Flour is the main ingredient and the primary determinant of quality, assuming consistency in the process. Flour quality is determined by the vitreous properties of the wheat kernel, which maximize semolina output in milling.

It is further defined by the ability of the semolina flour to be processed into quality pasta.

This quality is further described by a desirable amber yellow colour in the wheat, a gluten structure that allows extrusion or sheeting into relatively thin, but strong sheets and an end product with acceptable cooking quality when the pasta is prepared for consumption.

Colour is largely related to the genetics of the wheat and determined during wheat breeding programmes, when durum wheat varieties are developed. Cooking quality is defined by the surface and texture or stickiness of the pasta after cooking.

Cooking qualities are mainly a function of protein quantity and quality. The protein and gluten levels of durum flour have been found to correlate with the quality of the pasta produced from the flour.

Typically, durum flour with at least 12% protein is necessary to provide the quality characteristics required of most pasta. Protein quality is complex and more difficult to define.

However, good correlations have been found between protein quantity – more specifically the quantity of gluten protein – and the cooking quality of pasta (Fabrini and Lintas, 1988). Numerous procedures have been suggested for evaluating pasta gluten (Fabrini and Lintas, 1988).

The resilience of cooked pasta is largely determined by gluten characteristics, and Feillet et al. (1977) demonstrated that varieties with strong gluten exhibit high elastic recovery and good cooking quality while those with weak gluten show low elastic recovery and poor cooking quality.

A high glutenin-gliadin ratio or a high soluble protein content also improves cooking quality (Fabrini and Lintas, 1988). To sum up, protein attributes are the primary determinants of the firmness, stickiness and cooking quality of pasta.

Pasta quality tests include cooking tests to determine actual product quality, tests to evaluate wheat characteristics, milling tests and physical tests for flour quality (Fabrini and Lintas, 1988).

Wheat evaluations include test weight, 1000- kernel weight and vitreous kernel content. Milling tests are used to determine extraction and the appearance and granulation of semolina.

Other physical tests include protein, ash, moisture, falling number and pigment content. Wheat breeders use the Mixograph, sedimentation tests and protein evaluations to predict the performance of pasta from durum wheat cultivars.

These tests also have applications as durum flour quality tests. Finally, pasta is evaluated for colour with a colorimeter, firmness with an instrument that measures force such as the Instron (Instron Corp., Canton, MA) or TA-XT2 (Texture Technologies, Scarsday N.Y.), cooked weight, and dry soluble residue left in the cooking water as compared to standards.

B. Faults in Pasta: Their Causes, and Ways of Preventing Them

By : V. Webers and G. Schramm

Dry pasta or noodles are products of any shape made from cereal flour with or without the addition of egg and/or other ingredients by dough formation, shaping and drying without a fermentation or baking process.

Fresh pasta is dried only superficially, or not at all, during the production process. Both types are sometimes treated with hot water or steam (before drying; see chapter on Instant Noodles).

Certain requirements and conditions have to be fulfilled in the production of pasta as in any other food production process. They fall into the following general categories:

• Raw materials

• Method

• Plant and equipment

• Know-how.

The raw materials are the basic requirement for production; they largely determine the method and equipment to be used and therefore make specific demands on the knowledge, experience and skill of the persons who handle them.

The method and the technical equipment are two aspects of the same question: on the one hand thought must be given to the raw materials to be incorporated in the product and a suitable method chosen; and on the other hand special knowledge is needed to develop and specify the technical equipment for making these raw materials up into the product.

Since the production of pasta is a highly mechanized process, the quality of the finished product depends to a great extent on the manufacturer's know-how and his ability to control the process correctly.

Out of this complex of questions we shall consider those that have to do with the raw materials and are relevant to the quality of the end product and any faults that may occur.

In spite of considerable successes in the breeding and selection of soft and hard wheat Triticum aestivum and technical progress in pasta production, the raw material of choice for making high-quality dried noodles is still durum wheat T. durum.

|

| Tab. 132 : Causes of faults in the finished pasta and ways of preventing them: appearance and shape of the pasta before cooking |

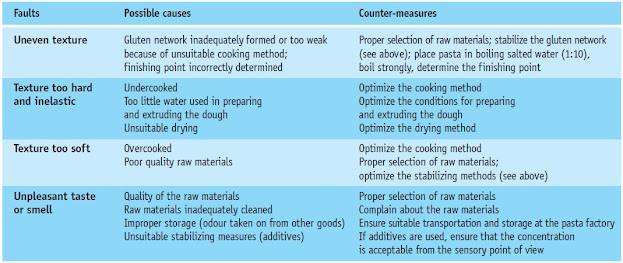

Tab. 132 and Tab. 133 show the negative effects of raw materials and processing on the properties

of the boiled pasta, and possible ways of preventing them.

Tab. 134 summarizes faults in the cooked pasta in respect of taste and smell.

|

| Tab. 134 : Causes of faults in the finished pasta and ways of preventing them: sensory quality |

No other cereal has the entire complex of raw material attributes offered by durum wheat. But with durum wheat, too, the quality that can be achieved in the finished product depends on selection of the raw materials, proper treatment at the mill and the production process.

|

| Fig. 216 : Comparison of spaghetti made from bread flour (left) and durum wheat (right) |

|

| Fig. 217 : Cracks in spaghetti made from soft wheat (left) caused by drying too quickly. On the right, slowly-dried pasta by way of comparison. |

The photographs show some typical shortcomings in the quality of extruded pasta: a dark, unattractive colour resulting from the use of poor-quality soft wheat flours (Fig. 216), cracks resulting from harsh drying conditions (Fig. 217); and blisters caused by the inclusion of air bubbles as a result of an inadequate vacuum in the mixer (Fig. 218).

|

| Fig. 218 : Blisters in soft-wheat spaghetti caused by an inadequate vacuum during mixing. |

Tab. 132 shows the negative effects of raw materials and processing on the properties of dried pasta, and possible ways of preventing them.

As we said before, important as it is to ensure high-quality raw materials, this is not the only factor on which the production of good pasta depends.

Raw materials, shaping dies, plant, technology and qualified operating personnel interact in a complex manner and result in an end product that is excellent or less satisfactory.

Tab. 135 lists desirable properties of flour as raw material for pasta and noodles.

|

| Tab. 135 : Recommended attributes of raw materials as a condition for producing good-quality pasta |

References

• Alden L, 2003. The Cook's Thesaurus. Asian Noodles: http://www.foodsubs.com/Noodles.html.

• Ang CYW, Liu KS and Huang, YW, 1999. Asian Foods Science & Technology. Technomic Publishing Co., Inc. Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

• Anon., 2004. Japan Convenience Foods Industry Association. Instant Ramen's Dictionary: http://www.instantramen.or.jp/english/.

• Daniel D, Anderson M, Barker W, Facto H and Hatcher D, 1998. Asian End-Product Testing at the Grain Research Laboratory. Canadian Grain Commission, 600-303 Main Street, Winnipeg MB R3C 3G8C, Canada.

• Fabrini G and Lintas C, 1988. Durum Chemistry and Technology. American Association of Cereal Chemists, St. Paul, Minnesota, U.S.A.

• Feillet P, Abecassis J, and Alary R. 1977. Description d'un nouvel appareil pour mesurer les proprieties viscoelastiques des produits cerealiers. Application a l'appreciation de la qualite du gluten, des pates alimentaires et du riz. Bull. Ec. Fr. Meun 273:97.

• Guo G, Shelton DR, Jackson DS and Parkurst AM, 2004. Comparison study of laboratory and pilot plant methods for Asian salted noodle processing. J. Food Sci. 69(4):FEP159-163.

• Herbst ST, 1995. The food lover's companion, 2nd edition. Barron's Educational Services, Inc.

• Hou G and Kruk M, 1998. Asian Noodle Technology. AIB (The American Institute of Baking) Technical Bulletin. XX: 12, Manhattan, Kansas. International Ramen Manufactures Association (IRMA). IRMA Factbook. 2003.

• Kim SK, 1996. Instant noodles. In: Pasta and Noodle Technology. Kruger JE, Matsuo RB and Dick JW (eds.), AACC Inc., St. Paul, MN, USA Oh, NH, Seib PA, Deyoe CW and Ward AB, 1983.

• Noodles. I. Measuring the textural characteristics of cooked noodles. Cereal Chem. 60:433-438.

• Parkinson R, 2004a. Chinese Cuisine: http://chinesefood.about.com/gi/dynamic/offsite. htm?site= http://www.saturdaymarket.com/chinabreakfast/ handnoodle.htm.

• Parkinson R, 2004b. Chinese Cuisine: http:// chinesefood.about.com/ library/blrecipe137.htm.

• Shin SN and Kim SK, 2003. Properties of Instant noodle Flours Flours Produced in Korea. Cereal Food World Res. 48(6):310-314.

Post a Comment